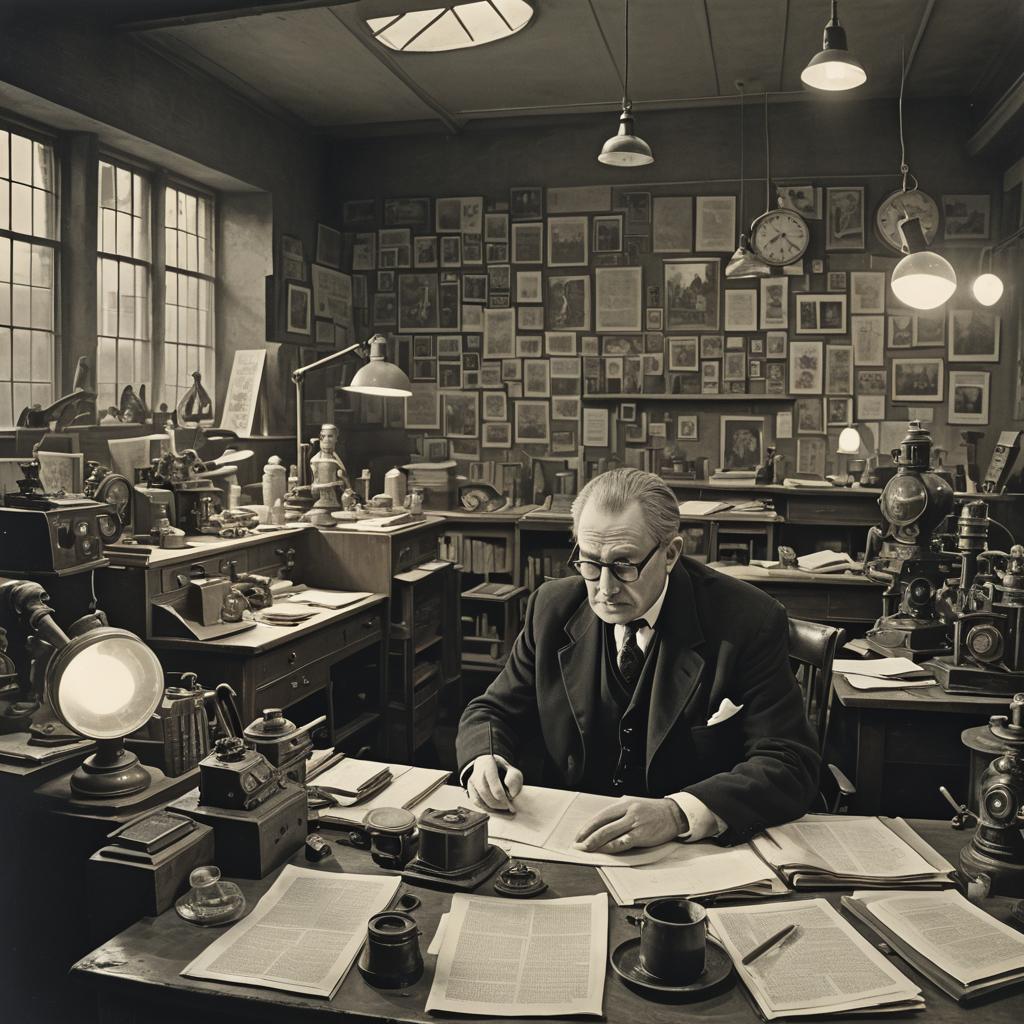

The Decline of Practical Skills

and Industry in the UK: A Middle-Class Paradox

Over the past several decades, the middle class in the UK has played an influential role in shaping the direction of the nation’s culture, education, and industry. However, there is an increasing argument that this group has become disconnected from the practical realities of modern life, prioritizing academic credentials over essential, hands-on skills and allowing crucial industries to fall into decline. This article explores how this cultural shift has led to diminished learning opportunities, less efficient management, and a significant erosion of British industrial power, focusing on sectors such as motorcycling, the car industry, and hosiery.

The Overemphasis on Academia at the Expense of Practical Skills

One of the key criticisms of the UK middle class today is their prioritization of academia over practical skills. For decades, there has been an almost unyielding emphasis on achieving academic credentials, often at the cost of learning practical skills. The ideal of a university education has been romanticized to such an extent that it has overshadowed the importance of vocational education and training.

This mindset can be traced back to the post-war era when grammar schools and comprehensive education reform began to shift the nation’s focus towards creating a professional workforce. At that time, such a strategy seemed appropriate as Britain sought to rebuild itself after the devastation of World War II. However, the pendulum swung too far, and the prestige of academic achievement quickly began to eclipse the value of skilled labor.

In the present day, we see the consequences of this imbalance. Despite the need for highly skilled tradespeople, engineers, and technicians, there remains a shortage in these sectors. Apprenticeships and vocational training have been marginalized, seen as secondary or inferior to obtaining a university degree. As a result, many young people are channelled into higher education, often accruing substantial debt in pursuit of degrees that do not necessarily provide the skills needed in the job market. Meanwhile, the industries that require hands-on expertise suffer from a dearth of talent.

Diminished School Hours: A Growing Concern

Compounding this issue is the steady erosion of effective school hours in the UK. Over the years, school days have become shorter, and holidays longer, resulting in less classroom time dedicated to essential learning. The reduction in instructional time has a significant impact on both academic and practical skill acquisition.

Studies show that the amount of time students spend engaged in meaningful learning activities directly correlates with their academic performance and skill development. Yet, despite these findings, UK schools have continued to cut back on classroom hours. Teachers often find themselves stretched thin, juggling large classes and a curriculum that is frequently revised to focus more on exam results than on actual learning.

As a result, students are not only losing out on core academic subjects but also on practical skills that are essential for the workforce. Woodworking, metalworking, home economics, and other hands-on subjects have been phased out of many schools altogether. This trend reflects a broader cultural bias that favors theoretical knowledge over practical capability, a bias that is perpetuated by the middle-class management of educational policy.

Middle-Class Management and the Decline of British Industry

Beyond education, the impact of middle-class management on British industry has been equally detrimental. From the 1950s to today, middle management—primarily populated by the middle class—has struggled to effectively modernize and sustain key industries, leading to a pattern of decline across multiple sectors.

The British car industry is a prime example. Once a global powerhouse, the UK’s automotive sector has been marred by poor management decisions, lack of investment in innovation, and failure to adapt to changing global markets. Throughout the latter half of the 20th century, British car manufacturers like British Leyland struggled with inefficiency, outdated practices, and a management class that often seemed more concerned with maintaining the status quo than with embracing new technology or processes.

A similar pattern can be seen in the British motorcycle industry. In the post-war years, the UK was home to some of the most respected motorcycle brands in the world, such as Triumph, BSA, and Norton. However, by the 1970s, these brands were floundering, unable to compete with more innovative and efficiently managed Japanese manufacturers. The reasons for this decline are manifold, but a significant factor was the complacency and short-sightedness of middle management, which failed to recognize the importance of research and development, modernization, and adapting to consumer demands.

Another example is the hosiery and textile industry, which was once a cornerstone of British manufacturing. Here, too, we see a story of decline driven by mismanagement, lack of foresight, and resistance to change. As global competition increased and new technologies emerged, many British textile firms remained stuck in outdated practices, unable or unwilling to innovate. The result was the loss of thousands of jobs and the erosion of an industry that had been central to the UK’s economic identity.

The Wider Impact on Other Industries

This pattern of poor management extends beyond motorcycles, cars, and hosiery. The steel industry, for example, has also suffered from decades of neglect and poor decision-making. Despite being one of the key building blocks of modern infrastructure, the UK steel industry has been allowed to wither, with a focus on short-term profits over long-term sustainability. The collapse of the British coal industry, too, was not merely a matter of economic forces but also a failure of middle-class management to anticipate changes and pivot accordingly.

Failing to Modernize: A Lack of Vision

The common thread running through these stories of industrial decline is a lack of vision from the very people who should have been guiding these sectors into the future. Middle-class managers, often insulated from the practical realities of the industries they oversee, have failed to recognize the need for modernization and innovation.

In many cases, middle management has been characterized by a risk-averse, conservative mindset. Rather than investing in new technologies or exploring new markets, there has been a tendency to cling to traditional methods and practices. This aversion to change has left many British industries lagging behind their international competitors.

Moreover, there has been a lack of accountability. In many instances, middle-class managers have been able to avoid the consequences of their failures, protected by their networks, credentials, and the very culture of credentialism that they have helped to cultivate. This has created a culture where mediocrity can thrive, and true innovation is stifled.

The Cultural Disconnect

A further issue is the cultural disconnect between middle-class management and the working-class individuals who actually operate the machinery, build the products, and drive the productivity of these industries. Middle management often lacks a genuine understanding or appreciation of the practical skills and knowledge that are necessary to keep these industries running effectively.

This disconnect is reflected in the increasing reliance on consultants and external advisors who often bring little practical experience but come armed with abstract theories and management jargon. These consultants are typically middle-class professionals themselves, further perpetuating a cycle where practical, on-the-ground knowledge is undervalued.

What Can Be Done? Rebalancing Education and Industry

To address these issues, there needs to be a fundamental shift in the way we value education and skills in the UK. A return to valuing practical skills alongside academic achievement is essential. This can begin with reforms in the education system that reintegrate vocational training into the curriculum and provide equal opportunities for students to pursue either academic or practical paths based on their interests and abilities.

Additionally, there needs to be a push to modernize British industries, with a focus on innovation, sustainability, and adapting to a changing global market. This requires not just investment in technology but also a willingness to embrace new ways of thinking and doing things. Middle management must be held accountable for their decisions and incentivized to prioritize long-term growth over short-term gains.

Moreover, there needs to be a cultural shift within middle management itself, one that values practical experience and hands-on knowledge as highly as academic credentials. This means breaking down the barriers between different classes and fostering a more inclusive approach to decision-making in industry and education alike.

Conclusion

The UK’s middle class, in its pursuit of academic credentials and professional status, has lost sight of the importance of practical skills and effective management. This has had a profound impact on both education and industry, leading to a decline in key sectors and a loss of valuable skills. To reverse this trend, there must be a reevaluation of what we value as a society, a move towards rebalancing education, and a renewed commitment to innovation and modernization in all areas of industry. Only then can the UK hope to regain its status as a leader in the global industry and education.

Share this content:

Post Comment